“Do not just try: do things, even if you do them wrong”

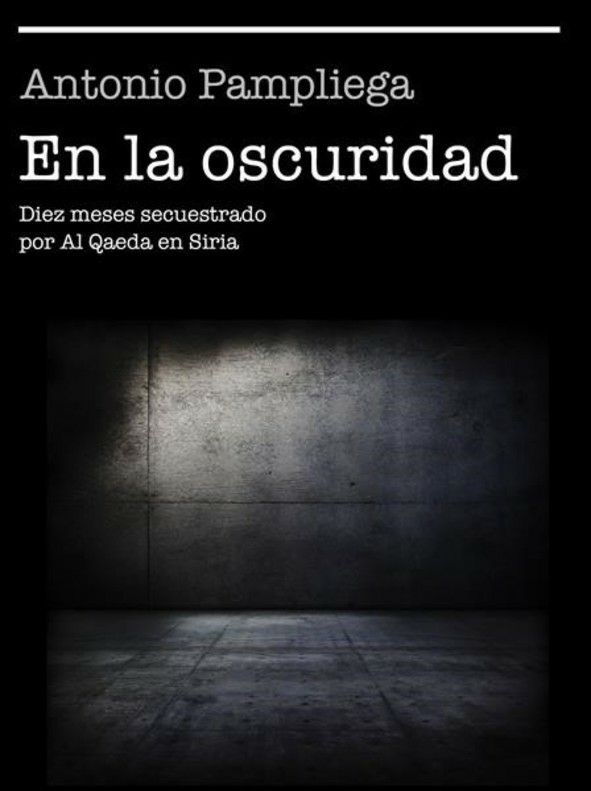

While he was covering war in Syria in July 2015, Antonio Pampliega was kidnapped by Al Qaeda, together with two other spanish journalists: Ángel Sastre and José Manuel López. Isolated from them, Antonio spent most of those 299 days in full solitude. He intended suicide and suffered a fake execution. Finally freed in May 2016, he published a book entitled ‘En la oscuridad’, based on the diary he wrote for his little sister while he was kept captive. Antonio will appear in the multiconference events organised by De los Pies a la Cabeza.

- You lived one life before the kidnapping, a whole different one after it.

- Yes, in my existence there was a before and there is an after, for good or wrong. Some traumas will be there with me for the rest of my life, even though I put loads of work on them. But there is a bright side to it too: a lesson I will not forget. Now I place a much bigger value on things like spending time with my family. For me, work is not anymore above life anymore. I still travel, but my trips are now shorter. I’m putting other things first.

- How does such an experience change a human being?

- Eventually, the idea of an execution became liberating for me: It meant the suffering would cease, I could stop crying my days out, full with fear… Then, when I thought everything was over, a new life started. Dealing with that is not easy. There is euphoria at first, but then you have to go through the whole thing very carefully. Returning to the real world, after being removed from it for 10 months, takes some time. You can overcome anything and you have to live on with it… You must do so. No matter what.

- Living within your circumstances, not against them or off them…

- My life did not finish when I got kidnapped, neither after mi liberation. I hope I have many years left in front of me. But you need to manage the whole thing. The human being can get through a lot. I never thought I could overcome a kidnapping, but I did. And every single day while I was captive, I had to cope with the possibility of being assassinated next day. Nobody is ready to die, but you finally assume it, you adapt yourself to it and you get ready for it. After that, you can’t step off the world, life goes on. So my message will always be a positive one: never give up. Never. Take it from me: I did give up and lied on the floor, ready to die.

- Can we only take that strength through an extreme experience like yours? Don’t we humans ever learn?

- Something I can say is that, obviously, we will all eventually die. When I started working in war areas, that was the first thing I had to come to terms with: I could die and I could be kidnapped… just because it had happened to other people, it happens all the time. But when it finally happens to you, your whole perspective shifts. That is why there is a message I really want to put forward to everybody: be ready to die, but do it in joy… so to speak. We have to live joyfully every day. It could all end tomorrow.

- How did you accept that could be your case? End tomorrow?

- During that time I used to think of all those things I had missed through the years. Things I had not done with my parents or my family. Trips I had not taken with my little sister. And I knew maybe I would never be able to make up for that anymore. Unfortunately we have to go through some limits to be aware of all this. But we shouldn’t. All the time while I was held captive I remembered how I hug my father goodby, at the airport, on the 8th of July when I flew off Spain. And I missed that moment because I couldn’t know if I would be able to ever hug my father again. The only thing that matters in life is to enjoy it with the people you love, and not allow opportunities to be missed.

- It is said we fear death, but we might actually fear living even more…

- There is not turning back and one day you’re going to find you have spoiled your life. My theory is: do it or don’t do it… but don’t just try. And, above all, do not regret what you have not done. Do things, even if you do them wrong. Just do them. Sadly, people don’t take this message in full, because they don’t want to expose themselves. But one day they will realize that it is worth taking risks.

- Is it worth taking the risk of going into war areas?

- I do it because I’m not fond of data. In fact, I don’t like numbers, since they hide the person behind. With my work I help put a face to those people. Take a soldier boy… I look at him and see the kid, with his fears and uncertainties. A kid who tells you that he was forced into a control post in Aleppo, and he will kill if necessary… but what he really would like is going to school. In a hospital in Mogadiscio, where little babies starve to death, I see mothers who have lost three or four of their children and still they cannot cry. “It is life”, they tell you. “I have lost three but I still have three more… and maybe some more are still to come if that is God’s will”. We the journalists are the voice of them who can’t talk, and the eyes of them who can’t see.

- How do you turn back to the western society after seeing that kind of thing?

- You feel funny. In the western countries we get crossed for the foolest reasons… be it a waiter or a supermarket clerk who keep you waiting. And I’ve seen people queuing for hours just to get a bottle of water. There we have opposed realities, but luckily enough I was born this side of the wall.

- How do you reconciliate with those two realities?

- It takes some effort to get used to it, but you have to. Otherwise we would not be able to live in our society. That is what happened to Kevin Carter, the photographer who famously took the picture of the bird lurking the little girl during the 90’s famines in Sudan. He couldn’t cope with the whole thing and killed himself. It takes a lot, but you must do it. I will never be an afghan or a syrian or a somali… and with the fullest respect, I don’t want to.

- Do you get cynical or more critical of our society after seeing reality in those other societies?

- We have loads of good things in the western societies. But there are many bad ones as well: we are egoists, egocentrics and egotists… We only think of ourselves and not the others. Once my translator in Afghanistan came to visit Spain and he said to me: “Antonio, we in Afghanistan are one of the poorest countries in the world, but we don’t have people begging in the streets, as happens here. When the night comes, we open the doors of our houses and give them a bed”. That is exactly so: you see no beggars spending the nights in the streets in Kabul. That is a lesson they can teach us.

- We are egoists, but loneliness is our biggest fear.

- The hardest part of the time I spent kidnapped were not the threats, the beatings or even when they faked my execution. The worst part was being all alone. Not having nobody to talk to. First when we were captured we were together, the three of us. We kept in company, we could talk… and that was a relieve. When I got isolated from my colleagues, there was nobody to talk to, I didn’t know what had been of them, and I couldn’t even leave the room and go in the streets to see other people. In fact I did not want to see the only people who came into the room, cause they were my captors. That is very, very hard. No human being should live in solitude. I thought of those old people who have nobody by their side and ring a number only to get somebody they can talk to. All I could do is what I did: I talked to God; and I wrote a diary to tell my litle sister how lonely my days were. Anything to keep me away from madness.